Declarative Protection, Real Violence: What Is the Experience of the LGBTIQ+ Community on Major Online Platforms?

Although major online platforms generally have policies intended to protect the rights of the LGBTIQ+ community, experiences from the Western Balkans show that these policies often remain only words on paper. Hate speech, threats, and coordinated attacks against the LGBTIQ+ community in the digital space have become an everyday occurrence, while responses from platforms and institutions are delayed or entirely absent.

Photo: Zašto ne

For the purposes of this article, interviews were conducted with Bojan Lazić (Da se zna) and Lejla Huremović (member of the Organising Committee of the BiH Pride March)

LGBTIQ+ persons around the world are often exposed to various forms of online violence. At the same time, the online space remains an extremely important place for socialisation, exploration and understanding of identity. For this very reason, protecting this community from technology-facilitated violence should be a priority.

According to the publication “Research Report on Online Violence and Online Hate Speech Against LGBTI Persons in Bosnia and Herzegovina”, published in 2024 by the Sarajevo Open Centre (SOC), a civil society organisation focused on advancing human rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the majority of respondents who identified as LGBTIQ+, and were included in the research, had been exposed to some form of online violence and hate speech.

Respondents stated that the most common places where they were exposed to such violence were online portals, social media platforms and messaging applications such as Viber. In other words, the violence occurred while using major online platforms that, declaratively, have policies and rules in place intended to protect the LGBTIQ+ community. Such policies exist on platforms operated by Meta, TikTok, and Snapchat and even on applications such as Viber. Some of these policies explicitly refer to the LGBTIQ+ community, while others include bans on abuse and hate speech based on sexual orientation.

However, experience in the region (1, 2) and beyond (1, 2) shows that online violence occurs very frequently. This demonstrates that the aforementioned policies are largely declarative and that their actual implementation is lacking. As Bojan Lazić from the organisation “Da se zna”, which provides legal and psychological support to LGBTIQ+ people, points out, hate speech and threats have almost become a daily reality for the LGBTIQ+ community in the online space. Such cases, Lazić says, intensify especially when someone from the community has a public appearance. From the personal profiles of activists and the profiles of organisations working on community rights, to comments under media articles that in some way address LGBTIQ+ issues, such comments have become unavoidable.

As for reporting content to major online platforms, part of the community has given up. The reason is the chronic lack of adequate responses from major online platforms to such reports. Responses are either non-existent or consist of generic replies stating that the reported content does not violate platform policies.

The majority of respondents, according to the aforementioned SOC publication, were not satisfied with responses to reports of harmful online content submitted to major online platforms.

“The responses of social media administrations were minimal, in the form of generic replies without concrete actions, or non-existent; meaning that social media administrations rarely removed threats”, the publication states.

Responses in this area are also often lacking from competent institutions. In Serbia, for example, there is a Special Prosecutor’s Office for High-Tech Crime, an authority to which high-tech crime offences can be reported. However, although the body formally exists, its responses to reports related to threats and endangerment of the safety of the LGBTIQ+ community are slow and often non-existent. Any response from the Prosecutor’s Office sometimes arrives months later, and the impression is that it is merely “checking the box” – in other words, formally fulfilling an obligation without a genuine intention to act substantively.

“Creative” Strategies for Targeting the Community on Major Platforms

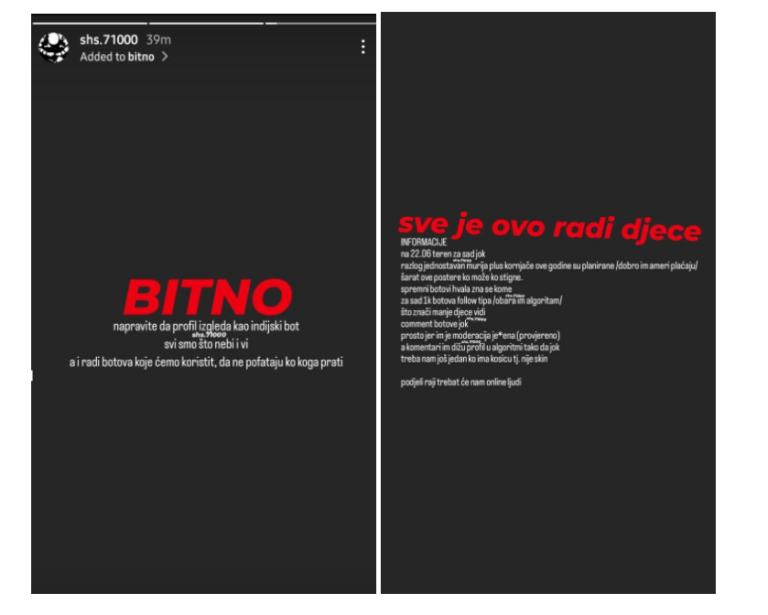

Ahead of the 2024 Pride March, the Pride’s Instagram account, which was actively used for campaigning and public communication, was attacked with the aim of reducing its reach. Individuals who opposed the organisation of the Pride March and endangered the community’s rights attempted to undermine the account’s reach by organising a large number of people to follow the profile simultaneously. Such inauthentic behaviour is meant to send a “warning signal” to the platform, which may then reduce the reach of this profile.

As can be seen from screenshots provided to us by Lejla Huremović, a member of the Organising Committee of the BiH Pride March, in addition to public calls to “follow” the account, malicious individuals also paid for “bots” to follow the Pride profile.

Photo: Screenshot

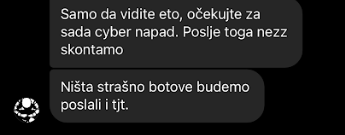

Such unnatural and rapid growth in followers can be interpreted by Meta as inauthentic behaviour, prompting the platform to impose restrictions on the account. This is precisely what happened to the Pride March account. The organisers of this targeting campaign even “bragged” about it to the administrators of the Pride March account, sending them a video showing the sudden spike in followers.

Photo: Screenshot

This attack had serious consequences for the Pride March. Their Instagram reach was limited for days. They were unable to resolve the issue through publicly available communication channels with the platform and only regained their reach with the help of intermediaries who had the ability to communicate directly with the company.

An attack following the same pattern recently occurred against student blockade in Serbia. Malicious actors across the region thus use the same well-tested tactics of abusing major online platforms to target those with opposing views.

Non-Implementation and Regression of Platforms’ Own Policies

Major online platforms are also inconsistent in applying other policies of their own. A test conducted in Ireland by the research organisation Global Witness showed that almost all advertisements containing “extreme violent hatred” against LGBTIQ+ persons were approved on TikTok, Facebook, and YouTube.

“Ten ads were submitted to all three platforms (all were removed before publication) and contained malicious and hateful language, including examples based on real cases reported by LGBTQ+ groups in Ireland. They compared LGBTQ+ people to ‘pedophiles’, called for ‘all gays to be burned’, and demanded that ‘trans lobbies’ be ‘killed’. YouTube and TikTok approved all ten ads for publication, while Facebook rejected only two. All three platforms accepted an ad calling to ‘burn all gays’, as well as one encouraging men to commit violence against transgender women”, Global Witness states.

All three of the aforementioned platforms have clear advertising policies that prohibit and restrict such content (1, 2, 3). Thus, even in cases where clear policies exist, harmful content manages to bypass the mechanisms established by platforms and finds its way to online users.

An additional cause for concern is the trend of narrowing the scope of existing policies that are meant to protect users of major online platforms. For example, Meta announced in January of this year that it was changing its policies related to harmful content under the pretext of protecting freedom of speech. As a result of this change, numerous existing restrictions were removed, making it permissible, among other things, to describe LGBTIQ+ persons as “mentally ill”.

The scope of provisions related to the aforementioned inauthentic behaviour was also significantly reduced just a few days ago. Amendments introduced on 11 December, 2025 removed provisions on “inauthentic audience building”, which explicitly addressed the attack technique described above; by buying large numbers of followers to undermine someone else’s account.

From all of the above, it is clear that LGBTIQ+ people are often targets of various attacks in the online space, and that major online platforms are not doing enough to prevent such attacks or mitigate their impact. Online violence against LGBTIQ+ persons in the region takes numerous forms, including insults, threats, ridicule, discrimination, the publication of private information, the spread of disinformation, blackmail, and other dangerous practices.

Experience shows that platforms either lack adequate policies or fail to implement the ones they do have. Additionally, a trend of regression in these policies is evident, which significantly affects users, especially those from marginalised groups.

The Online Space Must Be Safer

The online space remains crucial for the socialisation of this community, which is often marginalised in Bosnian society. As stated in a text by Lejla Huremović published in August 2025 on the Mediacentar Sarajevo portal, “for many LGBTIQ+ persons in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the internet is not just a means of communication; it is often the first and only safe space for exploring identity, connecting with the community, and freely expressing oneself”. On the one hand, this space acts as a space of empowerment, while on the other, Huremović notes, “it can also become a source of violence, threats, and hate speech”.

“Bosnian-Herzegovinian society, as well as societies in the region, continue to stigmatise LGBTIQ+ people, preventing them from freely and naturally coming out and living authentically in the offline sphere, which is why the online space becomes the place where they socialise, come out to someone for the first time, and feel free to share their identity”, the aforementioned Mediacentar article emphasises.

Major online platforms are clearly very important for users. Precisely for this reason, attacks that weaponise the restriction of social media presence against them, such as the attack on the Pride March Instagram account, are particularly dangerous.

Therefore, protecting LGBTIQ+ community is crucial and must be an integral part of major online platforms’ policies, which must be applied consistently.

The European Union’s regulatory framework – the Digital Services Act – requires platforms to adequately prevent the spread of illegal content, which certainly includes certain forms of hate speech and discrimination. This entails clear and effective procedures for reporting such content, as well as prompt responses to user reports. Major online platforms, which include all the social networks mentioned above, are also obliged to regularly assess and mitigate risks arising from their systems, policies, or modes of use, in terms of enabling the sharing and amplification of illegal content, violations of users’ fundamental rights, and threats to their well-being, safety and physical and mental health. One example of a systemic risk is the described enabling or failure to prevent inauthentic behaviour, but this can also include a platform business model based on user profiling or inadequate content moderation practices that fail to take local language or context into account.

Citizens of the Western Balkans do not have the same level of protection on platforms. Introducing regulatory frameworks modelled on European ones is therefore a necessary step toward a safer online environment in which human rights and freedoms are protected.

(Marija Ćosić and Maida Ćulahović, “Zašto ne”)