Bosnian Fake News Fighters Take Heart

Knowing your foe is the first step in a campaign strategy, as a new study reveals. First in a series on disinformation in the Balkans.

Fake news, click bait, disinformation, misinformation, propaganda, conspiracy theories, pseudoscience – expressions like these are now permanent fixtures in our common vocabulary, signs that the information age also has its downsides. Balkan countries, in this field at least, are not falling behind the rest of the world. We, too, have our sophisticated foreign misinformation operations; Macedonia is the “proud” awardee of the title of fake news capital of the world; new online media outlets are popping up almost by the hour; and more and more people are reading the news on their phones.

What is lacking so far is well-grounded, reliable analysis of the state of disinformation in the region, as initiatives to increase resilience against manipulation of information are still in the early stages and are only just beginning to coordinate their efforts.

There are, however, several first indicators of why, how, and where media manipulations are spread. Recent research by my organization, the civic association Zasto ne (Why Not) and our fact-checking platform Rasrkinkavanje.ba, examined several aspects of disinformation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, reaching conclusions that also show some region-wide trends.

Many Ways to (Dis)inform

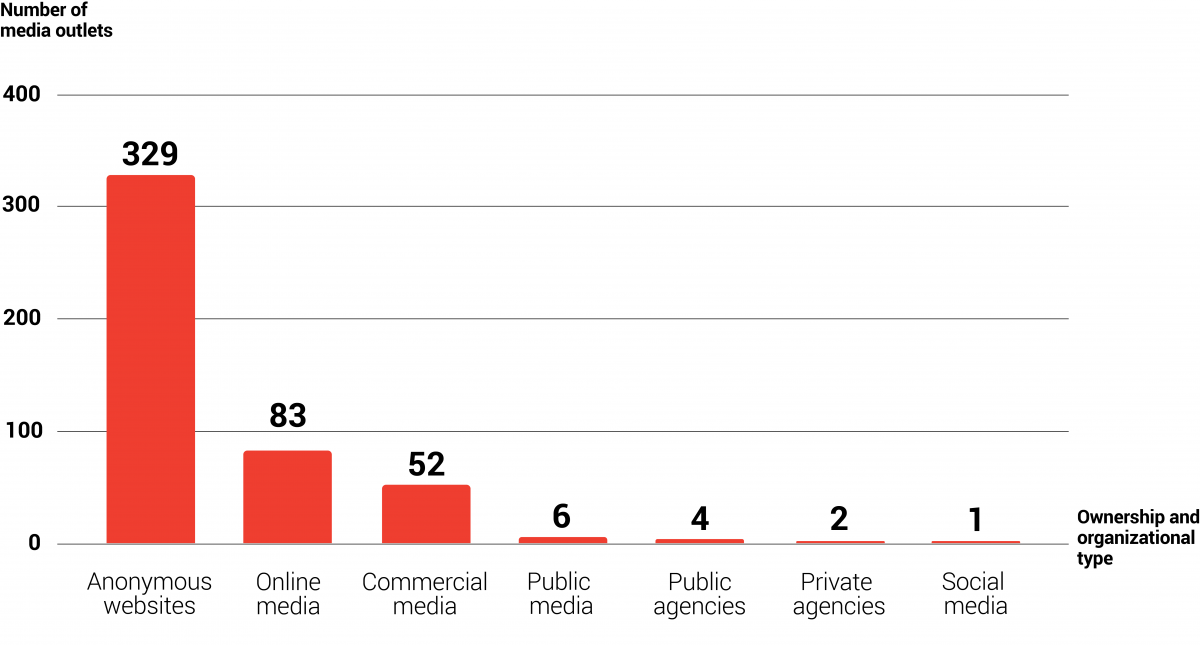

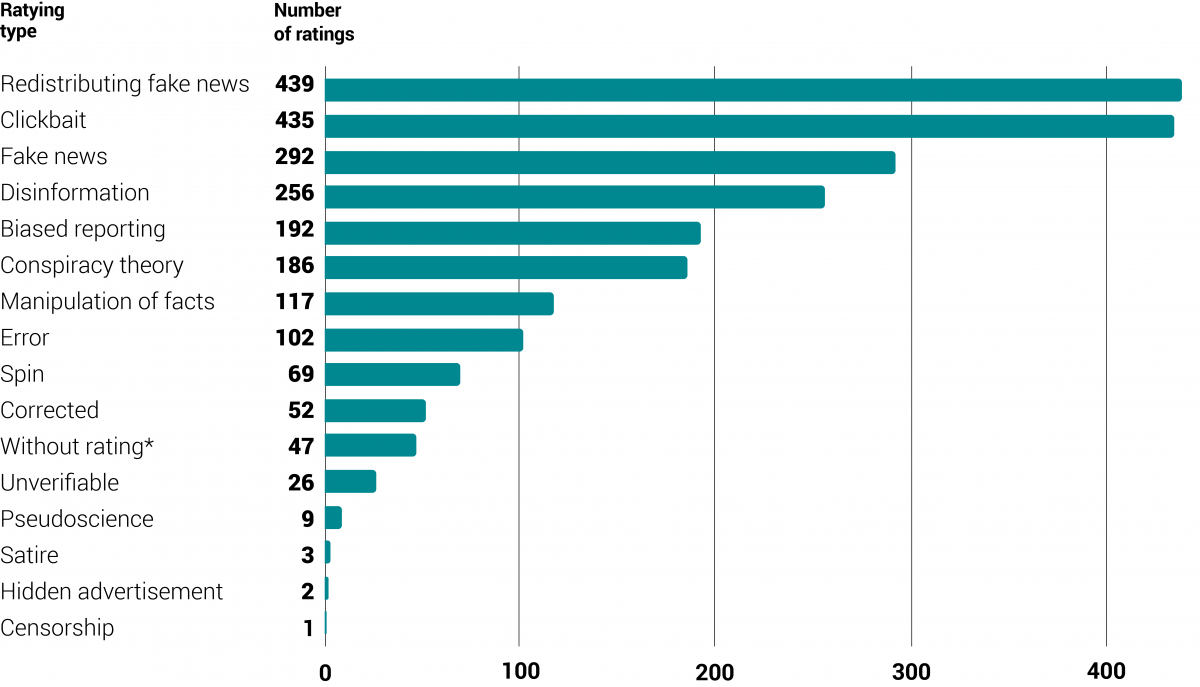

The study analyzed media reports for the use of 13 kinds of manipulation we considered to be harmful – from outright fake news to biased reporting, unverifiable statements, and satire that could be misunderstood as genuine news. Each report was checked for verifiable use of one or more of these categories of disinformation. In all, the study was based on 2,420 reports published by 752 different outlets between November 2017 and November 2018 where Raskrinkavanje.ba identified 3,592 uses of disinformation. Since the study’s main focus was on political news, the sample was further narrowed down to 1,486 reports in 477 outlets.

This research identified two main drivers for the use of deliberate disinformation in the Bosnian media: the financial motive, based on raising the number of consumers through what can be called “opportunistic disinformation,” and the goal of advancing political agendas by exploiting commercial and public media to spread disinformation. The study shows that the first motive prevails for the large majority of “anonymous sites” – operations that resemble news outlets but lack newsrooms, editors, and reporters, typically run by an individual or small group who keep their identities hidden.

The political motive appears most often in reports by public media and news agencies, but not only there – commercial and online media outlets also spread political disinformation. Although the majority of websites and social media accounts that spread disinformation are anonymous operations, established commercial and public media outlets are the main sources of disinformation.

The 10 main producers of disinformation identified in the study include only two anonymous sites, one of which was set up for targeted political purposes prior to elections in 2018. The main disinformation outlets in Bosnia are the public broadcaster for the Republika Srpska entity, RTRS, followed by the same entity’s public SRNA news agency and the private TV station Alternativna televizija, all part of the same “disinformation hub” – interconnected media outlets that jointly redistribute news both real and manipulated. The fourth biggest source is the first foreign media outlet on the list, the tabloid Informer from Serbia, another member of the same disinformation hub. Others include the newspaper Avaz (published by Bosnia’s biggest private media company) and two Serbian publishers, Srbija danas and Kurir.

The makeup of this list underlines that the biggest sources of disinformation in Bosnia and the region are not fly-by-night operations but established media companies with interests beyond simply increasing revenues through attracting larger audiences.

Our study also concluded that disinformation knows no borders. Easily distributed through a broad area with a shared or similar language, false or manipulated news spreads easily across the region. Media in most countries in the region act as producers, or more often redistributors of disinformation about issues in neighboring countries. The 477 sources of political disinformation about Bosnia named in the study included 100 which were definitely located abroad, many in Serbia.

Foreign influence in the disinformation sphere is still not something that local stakeholders consider seriously, although its workings are obvious throughout the region in many ways. In general, the problem of disinformation is also a problem of the lack of media professionalism and the scarcity of independent media at a time when new paradigms are becoming established in the digital world, where social networks and new media provide lucrative opportunities.

Although few people see this region as a theater in the global hybrid war arena, the reality is quite different. Sputnik Serbia’s role in spreading disinformation has been reported on several occasions since the Russian government-owned outlet began operating in the region four years ago. Its coverage of global geopolitical issues as well as local politics often seems to carry a subtext of seeking to influence the work of local media outlets. In Sputnik Serbia’s first year alone, Raskrinkavanje found 36 uses of disinformation in 16 articles, and 100 more articles were mentioned in another study by Raskrinkavanje as showing a clear bias towards the Bosnian Serb leader, Milorad Dodik. Other debunking groups in the region have also identified Sputnik as a disinformation source.

Locally owned outlets too clearly spread and amplify the pro-Russian agenda in many cases. A bias in favor of Chinese and Turkish positions is also obvious in some of the region’s media. This kind of influence on the media emerges clearly if we look at the targets and beneficiaries of certain disinformation pieces. Raskrinkavanje’s analysis shows that the United States, United Kingdom, and Israel receive the most negative mentions in disinformation content in Bosnia, while Russia and Germany benefit from generally positive coverage, the latter often portrayed as the most desirable country for economic migrants.

The previous U.S. administration receives a large number of negative mentions, with the names of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton leading the way. On the other hand, Donald Trump, conservative U.S. Representative Devin Nunes, and Vladimir Putin lead the positive mentions. Clearly, global disinformation narratives are being spread in Bosnia with the same topics and actors. However, the European Union is typically covered in a neutral fashion, although the contentious issue of EU accession is sometimes employed as a disinformation tool to discredit certain local politicians.

On the Farm

Another obvious problem with the local media is the prevalence of online outlets that adhere to no journalistic standards, in most cases existing solely to raise advertising revenue. With no monitoring of the region by the global tech giants, these outlets are flourishing and sometimes joining forces in informal “fake news farms.” Some “farmers” may own dozens of websites, activating or switching them off to stoke or damp down social media shares. For instance, a semi-anonymous online portal, novi.ba, has been linked with some 60 Facebook pages with a combined reach of almost 7 million users. There is an urgent need to implement Facebook’s fact-checking service and other tools to minimize this kind of manipulation.

The other critical factor is the indifference to the problem among decision- makers and other stakeholders – perhaps resulting from lack of information or attention to the issue or because some individuals benefit from the current situation. Much more work is needed to improve media literacy levels, whether by public bodies or other stakeholders.

Finally, as noted above, the most important aspect of the disinformation landscape in the region is the existence of disinformation hubs, loose networks that jointly distribute and redistribute identical items of manipulated news. These hubs include media of different types, and they cross national borders. The large hub mentioned earlier consists of 29 media outlets, 15 from Serbia and 14 from Bosnia (all but one located in Republika Srpska). The public broadcaster RTRS, the public news agency SRNA, and the anonymous site Infosrpska, together with Sputnik Serbia, are the main sources of disinformation in this hub, while commercial media such as Alternativna TV in Bosnia and Informer in Serbia, and a number of anonymous and other online media, act mostly as distributors.

All this allows us to say that a rough footprint of the disinformation problem in the Balkans is starting to appear, and there are a number of individual, mostly unconnected, efforts to tackle it. Looking ahead, these efforts need to be consolidated and connected, and strategies mapped out to address this issue on the regional and local level using appropriate means. International stakeholders, mostly civil society organizations, interested democratic governments, and tech companies, must also be an integral part of the solution. And all of us, the citizens of Balkan countries, need to become our own fact-checkers and learn how to differentiate credible from non-credible media and good news from bad, with help from the growing network of fact-checkers and journalists that pursue the values of ethics and integrity.

Written by Darko Brkan

Source: Tol.org