Open-source analysis: Foreign instigators and local amplifiers – Disinformation in Bosnia

The Balkans have made progress in tackling disinformation, but bad actors have grown more sophisticated.

As part of our effort to broaden expertise and understanding of information ecosystems around the world, the DFRLab is publishing this external contribution. We are building the community of #DigitalSherlocks. The views and assessments in this open-source analysis do not necessarily represent those of the DFRLab.

In recent years, a few initiatives have developed in the Balkans to increase digital resilience against disinformation. At the same time, both the sophistication and the volume of disinformation and media manipulation efforts has risen substantially. A fast-growing initiative called Raskrinkavanje (“unmasking” or “debunking” in Bosnian) has led the way in identifying and cataloguing known media manipulation campaigns targeting Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), as well as the wider region.

The study, “Disinformation in the Online Sphere — the Case of BiH,” looked into a database of a year of debunks done by Raskrinkavanje that consisted of 1,486 media reports by 477 media outlets proven to contain at least one example of media manipulation.

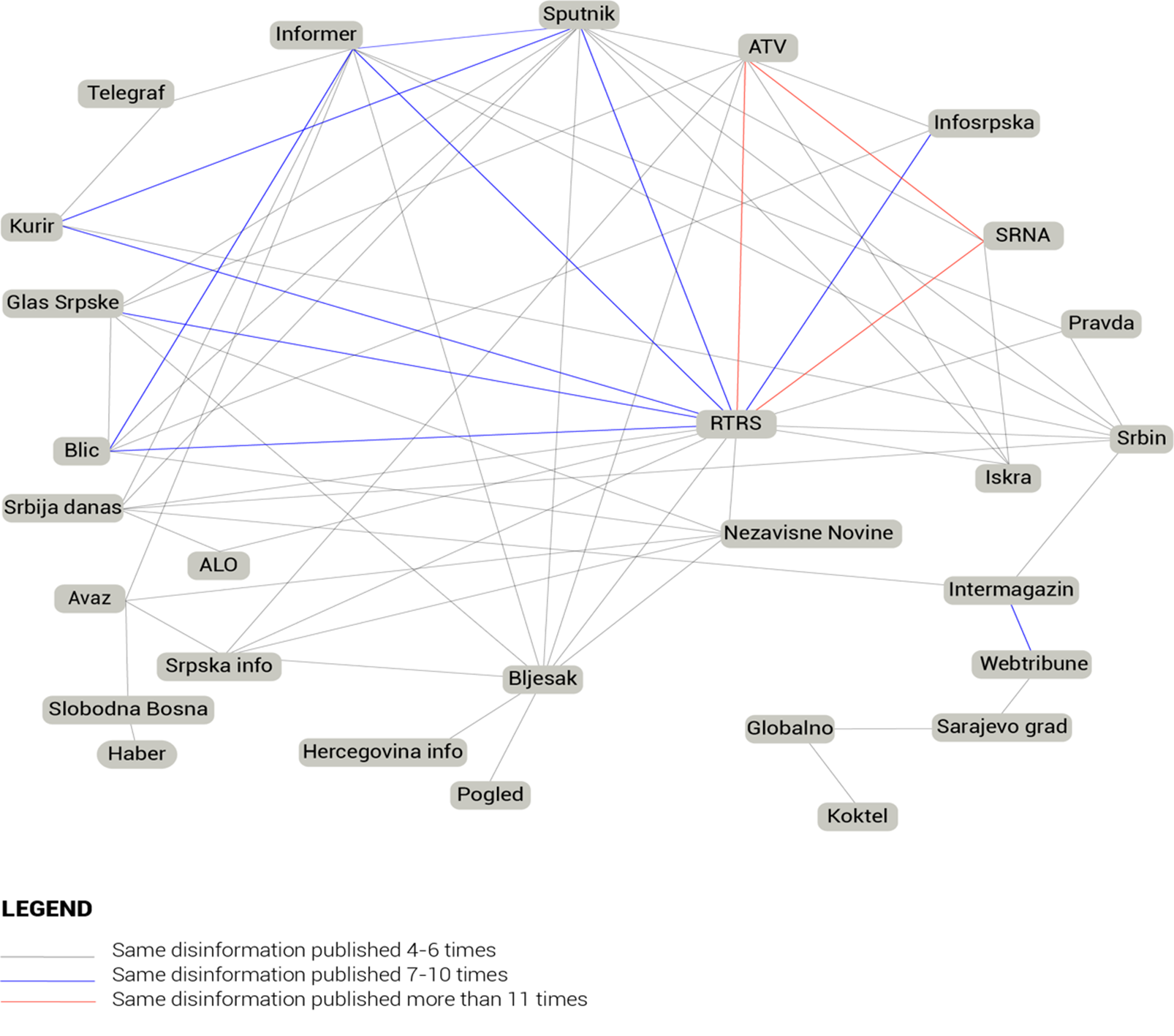

One of the most valuable findings of the study was the exposure of a “disinformation hub” of media outlets that frequently republished the same disinformation stories and spread similar messages. This hub consisted of 29 media outlets, almost completely coming from Republika Srpska (an administrative entity within BiH with a Serb majority) and Serbia. Based on the topics covered and the fact that is was most active in the months before the 2018 elections, it is safe to say that its’ goal was to instigate political and ethnic tensions in order to propel the agenda of the ruling party of Republika Srpska before the elections.

Among the outlets in the hub, only one was foreign owned: Sputnik Serbia. The government of Republika Srpska is openly allied with the Kremlin, which has the consequence of allowing the outlet to propagate its pro-Russian and anti-Western messaging without impunity.

The study also analyzed the links between the 477 outlets spreading disinformation and found that the links between these 29 outlets are, by far, more powerful than between any other media in the sample. These connections were measured based on the number of same disinformation published and republished by the outlets, as well as the importance and reach of the disinformation articles themselves. While it is impossible to prove coordination, based on the time and sequences of publishing and the number of the same reports published, it is also safe to say that there was obvious coordination between several of the main outlets in the hub.

This disinformation hub has been used for two main purposes: first, to propel the local position of the government of Republika Srpska and its largest party, SNSD, and its’ leaders; and, second, to promote pro-Russia messages and propagate anti-Western values.

This piece examines four examples of disinformation narratives disseminated by the hub. Two cases relate to BiH, one relates to the United States and Russia, and one relates to Serbia and Kosovo.

State-operated companies allegedly discriminate against Serbs

The first story, published in July 2017, reported that Pokop, a state-operated burial company from Sarajevo, was coercing the families of the deceased to pay the accumulated debts by marking graves for which the family failed to pay maintenance fees with stickers. Four months later, Glas Srpske announced that Pokop was preparing to exhume the graves of Serbs who had not paid in Sarajevo. Informer further claimed that excavation of 13,000 grave sites of Serbs had already begun.

In an article debunking this disinformation, Raskrinkavanje identified 16 media outlets from the disinformation hub that published this story, both in Serbia and in BiH: Sputnik Serbia, Informer, Blic, Alo, Kurir, Srbin info, Tanjug, Vesti online, Srbija Danas, RTS, Srbin, and Republika from Serbia; and RTRS, ATV, Glas Srpske, and SRNA from BiH.

This narrative used a conspiracy theory to portray state-operated companies in Sarajevo broadly as discriminatory of Serbs. The aim, as with a lot of disinformation targeting BiH, was to deepen the latent ethnic conflict between Bosnians and Serbs and to increase the negative attitude of the Republika Srpska population toward Sarajevo and its institutions.

Chomsky supposedly denigrated Albanians, called them “ungrateful”

The second story surfaced in January 2018, when SRNA, the state news agency of Republika Srpska, republished — and later deleted — an old false claim that U.S. philosopher Noam Chomsky had referred to Albanians as “a wild tribe” and described them as “ungrateful to Serbs in Kosovo who welcomed them to their territory.” The quote was a complete fabrication. Raskrinkavanje identified that the story was picked up by nine media outlets from the hub.

In putting forth this narrative, SRNA provided no evidence to support its claims. Such narratives are spread to aggravate the conflict between the Serbs and Albanians about the political status of Kosovo. Even if Republika Srpska had no immediate issue with Kosovo in this particular case, having its state news agency fabricate such a story can exacerbate ethnic tensions.

Denzel Washington purportedly praised U.S. President Donald Trump

In February 2018, the third story emerged: USA Liberty Press, a conservative website, published a (later debunked) claim that actor Denzel Washington had praised Donald Trump for saving the United States from a war with Russia and becoming “an Orwellian police state.” Anonymous portal Webtribune translated that article into the local language, while Sputnik Serbia produced a follow-up story asking several pundits to comment on the made-up statement. It also issued another fabricated story that added a local spin by connecting the made-up quote to an episode of a National Geographic show, “Story of Us,” about the Srebrenica genocide perpetrated by the Bosnian Serb army during the war in Bosnia, and implied that Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman (who narrates the program) are in dispute over Russia and Serbia.

Raskrinkavanje showed that the story was published in eight different media outlets from the disinformation hub, demonstrating how far an entity functioning as a hub can extend the reach of disinformation narratives and how foreign topics get reused for domestic audiences.

BiH is allegedly planning to attack Republika Srpska

Finally, in June 2018, a small cache of weapons and ammunition remaining from the 1992–1995 war was discovered during the demolition of an abandoned house in the village of Matuzići, a village in BiH. Two days later, SRNA reported, without any supporting evidence, that the cache had been found “in a warehouse” and “near a mosque” and failed to mention that the weapons were probably there because they stayed after the war. This change of narrative allowed SRNA, as well as other outlets to present this as evidence of “paramilitary formations from the Federation BiH stockpiling weapons for an attack on Republika Srpska.”

The false spin was picked up by 13 media outlets from the hub. The underlying narrative tactic was a common one: to use the imminent threat of lethal conflict to incite fear and hysteria in the population.

Sputnik Serbia’s role in the region

These cases also demonstrated the crucial role Sputnik Serbia plays in disinformation in the region. The outlet is based in Serbia but funded by and through the eponymous Russian parent company; the outlet produces and distributes content in the local language about and for the whole region of the Western Balkans and also provides news agency services, similar to the model used in other regions. Sputnik Serbia, however, might not be the biggest producer of disinformation in the hub — that distinction belonged to Republika Srpska public broadcaster RTRS, Republika Srpska’s state-owned news agency SRNA, and several commercial media outlets owned by people close to the government of Republika Srpska. Raskrinkavanje identified 124 pieces of disinformation disseminated by RTRS, 51 by the Alternativna TV commercial station, and 51 by SRNA, while Sputnik Serbia had only 36 instances of disinformation.

Sputnik Serbia is, however, together with RTRS, the most connected outlet in the hub, sharing disinformation articles with the most outlets in the hub. Additionally, Russia, like some other international actors, has proxies in BiH and neighboring countries. Thus, foreign disinformation efforts are spread not only via foreign-owned or foreign-funded media but also through local allies and proxies. That the government of Republika Srpska and its ruling party are open allies with the Kremlin ensures that these proxies operate freely.

In conclusion, the research revealed that the disinformation problem in BiH, as well as the region, needs to be understood as a hybrid threat and that there is low awareness of that fact among local stakeholders. The congruence of media disinformation and specific political interests raises concerns about targeted disinformation campaigns in the online sphere, some definitely related to foreign actors and sources, particularly Russia. Conversely, the key stakeholders have low awareness of such influences, despite being acutely aware of the overall problem of disinformation in the media.

WRITTEN BY @DFRLab

Darko Brkan is the co-founding President of Zašto ne (“Why not”), a civil society organization promoting accountability and participation, fact-checking politicians’ statements and promises, and combatting disinformation and media manipulation in BiH and southeastern